Georges Armaos is a director at Gagosian, London, where he has worked since 2006 focusing on emerging markets, institutional relations, and liaising with Anselm Kiefer’s studio. He has a PhD in art history and museology from Université Paris I, Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Erlend Høyersten is the director of ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark, and the founding director of the ARoS Triennial. He was previously director of KODE Art Museums in Bergen, Norway, and Sørlandets Kunstmuseum in Kristiansand, Norway, and holds a cand.philol. in art history from the University of Bergen. Photo: Lars Fredriksen

Georges ArmaosI’m very happy to be having this conversation today with you. We’re going to talk about three of my favorite subjects: ARoS, mythology, and Anselm Kiefer. ARoS is becoming better known, but it’s a place that is hard to get to. People don’t necessarily know that it’s the second most visited institution of its kind in Scandinavia. I would like you to talk about the museum, the building, which is essentially a landmark in the city, how you got there, and what you are doing as the director of the museum.

Erlend HøyerstenCopenhagen is more well-known, but Aarhus is the second largest city of Denmark. What I find fascinating about Aarhus (founded by the Vikings in 770 AD) is that it’s an old industrial city that used to be working class. In the last ten or twenty years, it has turned into an extremely interesting city for culture, art, and the creative industries. The museum has a long history that goes back to 1859. It opened as ARoS sixteen years ago. Since then, we have grown the number of visitors exponentially to 750,000 and we are gaining more and more international recognition.

One of the reasons I came to Aarhus is that there’s a great deal of flexibility in running the museum and shaping its culture. We have 25% government funding and 75% we generate ourselves. I started talking to politicians about the reasons we need art institutions like ARoS; they tend to think about culture as the cake of society. But culture is not the dessert, it’s the main dish.

I developed the idea of the museum as a mental fitness center, as a place where you can not only train your ability to see or think creatively, but also train your emotional intelligence, your ability to socialize, your ability to understand power structures, your ability to look through systems. What if we took that role to another level and started thinking about how we also can effect change?

So that was quite a big change for my staff, to start thinking about art as means and tools. Because we’re all taught to appreciate “art for art’s sake” and that art shouldn’t do anything, art shouldn’t be instrumentalized, because everybody’s so scared of art being misused by ideologies and politicians. The idea of the mental fitness center made it possible for us to reframe the role of art and the museum and develop new projects, for example the triennial in 2017.

GA The first triennial, in 2017, entitled The Garden, was a tremendous success. As always, when you hit upon a big success, you have to figure out a way to repeat it or move forward with something equally important. You and your team decided to grapple with mythologies. Why the subject of mythologies? How did you choose the works that deal with the subject matter?

EHWhen I decided upon the idea of mythologies, it was inspired by our experience and the feedback on The Garden. It was a logical step to go from nature to culture. I’ve been interested in the power behind storytelling since I was in university. There’s a common misconception of mythology as dead religions. You don’t think about Islam or Judaism or Christianity as mythologies, but they are. It’s society-constituting storytelling. For example, we were denied the loan of a biblical motif, a seventeenth-century painting, from an institution in the United States. The refusal letter said that they “don’t consider Christianity to be a mythology, so, no, sorry.”

Mythology is not only about religious systems. It’s also about political ideologies. So this exhibition touches upon the nation state, Nazism, Soviet communism, and we are also breaking ground by analyzing the welfare state; in the Nordic countries, the idea of the welfare state is very strong and everybody feels committed to it—well, not necessarily everybody. I love the idea that you actually have a system where you are helping and providing for people you don’t know. The welfare state, as a mythology, came under strain and people started focusing on their differences—in terms of religion, ethnicity, national origin—creating a kind of uncertainty and xenophobia that we see in various countries. People today feel alienated, not connected, not part of a bigger story. It’s really important to say that the bigger stories are already there, but it’s your role to pitch in and understand them and decide if you want to be a part of them or not. If people don’t understand how storytelling is working, they will be left behind.

At ARoS, we do exhibitions that challenge the way exhibitions have been done, challenging the status quo. Some people in the art world get aggressive because they’ve been believing in a system that looks like this and suddenly we are asking questions about why couldn’t we do it like that? People get very upset when you are testing what they believe in.

Our role is to make people interested and curious, and then they can go home, maybe visit a library, buy some books, go online and dig further, and start thinking differently.

—Erlend Høyersten

GAPart of the show is historical, starting with the Reformation and focusing on European art. The other part is dedicated to the way contemporary artists deal with the subject. How did you go about choosing which artists to include?

EHHonestly, it’s not only about the artists and the artworks, it’s also about how we talk about it and how we write about it. To be crystal clear, mythology is about society-constituting storytelling.

As you said, it’s a huge subject. We know that people will start asking how come you don’t have artists from there, and there? How come you don’t have mythologies from Latin America? From parts of Africa? As with The Garden, we’re not trying to tell the whole story—to be encyclopedic—rather we’re trying to find a core and we hope to expand upon it in the future. Our role is to make people interested and curious, and then they can go home, maybe visit a library, buy some books, go online and dig further, and start thinking differently.

We started by talking about the Greek myths. It’s quite an interesting starting point because there were many mythologies before the Greeks, but in the Greek myths, it’s the first time the gods actually look and behave like humans, with all their faults and abilities and jealousies and rage, behaving and misbehaving. That’s a very important turning point. It’s easier to talk about mythology when it’s not abstract, when it’s not a dragon or a kind of strange creature or a non-human god.

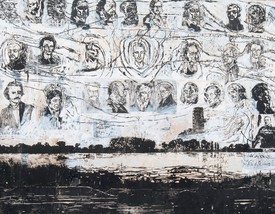

For the historical portion, we started with art from the Reformation movement, and then we got to the Counter-Reformation. We are not presenting Christianity as such, but we decided to focus in on specific times in the history during which mythologies clash. Catholic beliefs, Protestant beliefs, and the clash between these two worlds. Then we moved to the idea of neoclassicism, which becomes part of the French Revolution, the era of the Enlightenment. We moved to the idea of the nation state and how the ideas of the nation state are strongly corrupted when it comes to Nazism and Communism. Then going over to the welfare state and contemporary art. The question was what kind of artists have been actually working on these topics for a long time? In the beginning, you have hundreds of names. After a while, it becomes clear that we need to have this or that artist, that we can’t do a show without her or him.

GAAnselm Kiefer is one of the contemporary artists in the show. Tell me about your personal history of experiencing his work.

EHI remember the first time I saw a piece by Anselm Kiefer in person. Experiencing Kiefer live is something very different from seeing a reproduction of it in a book; it’s extremely massive. The first thing I remember was a big airplane that I saw at the Louisiana [Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark] in the mid-1990s. That was a “Whoa!!!” moment. Then I saw a work on permanent display at the old Astrup Fearnley Museet [Oslo]. I have never swum next to a big whale, but I reckon it’s the same feeling. You can really experience the presence of it. I remember the bookshelf and the old books you’re not able to read. You can’t turn the pages. It lends the idea that the presence of history is something that is not touchable.

Later on, he did that great show at Copenhagen Contemporary. So, I’ve been getting more and more curious about the way he works, because he works on a scale that is quite crazy. One sees the work and understands his generation. He grew up in postwar Europe in the shadow of the Nazi mythology, in a situation where you had a group of people trying to create a new mythology. And they succeeded. They created a new mythology that still has an effect on how we think and what we believe and what we support and what we don’t support, what we’re scared of and what we embrace in Europe. He’s part of a generation that I find fascinating, because there were a lot of people in Germany not wanting to talk about the war; they still felt ashamed about the war. I found it very brave of him to try to make these hugely complex issues physically understandable and less complex. The paintings have this kind of romantic sublimeness to them. Because they’re very beautiful, and at the same time, very scary.

GALet’s talk about the physical experience of his works. You have those three massive paintings inside one room. How do they look? How do you feel when you approach them, and what is striking for you in their physical presence?

EHI have the same experience every time I see his works. When you see them from a distance, with no people, they don’t look too big. When you walk toward them, you understand that it’s almost like an optical illusion. You have to walk a while and then they start growing; they become bigger and suddenly you understand that these works are extremely big, intense.

They are also extremely physical. I think people want to touch them. One of them is covered with straw and layered with gold. They have this great tactility. It’s like the works insist on being there.

GASo you’ve got those three big paintings with tough subjects, in typical Kiefer fashion. Väinämöinen – Aino (2016), a painting inspired by the Finnish Kalevala epic—an epic in and of itself, in that it became the foundation of the Finnish national identity in the nineteenth century. Then you have Sichelschnitt (Sickle Cut) (2019), the code name of the German invasion of France in 1940. You have böse Blumen (Flowers of Evil) (2018), which refers to Baudelaire’s Les fleurs du mal (1857). Brain-heavy topics, but also multidimensional titles that can send viewers in all directions. Beyond the physicality of the work, how do you think people are going to respond to the subject matter of the works in that specific environment in Northern Europe?

EHThat’s a good question; obviously I can’t answer it fully, but I’ll try to. From the outside, the Nordic countries are looked upon as being all the same, with the same culture, the same historical background. That is its own mythology.

As a Norwegian living in Denmark, I know that Danish culture is very different from Norwegian. The four big Nordic countries played totally different roles during the Second World War, for example. Becoming nation states, they had totally different kinds of births. Norway was in a union with Denmark (1380–1814), and later on with Sweden (1814–1905). Finland has been a colony under Sweden (1150–1809), and a Russia duchy (1809–1919). During the Second World War, Finland was neutral towards the Nazi party, but fought against the Soviets. Sweden was neutral but made a lot of money with Germany. I find it enormously interesting, because there are some stories that we are proud of in the Nordic countries, and others that we have to confront to understand what we became and why.

I believe a lot of museums will experience a renaissance. I think people will be eager to go back, understand that we have to reconnect, try to normalize. A lot of people will be in search of meaningful experiences, of quality, because they understand that life is fragile.

—Erlend Høyersten

GALet’s close this with the inevitable question around art after covid-19. What do you think is coming up for museums in general, under new social circumstances? The museum as a mythmaking machine in and of itself?

EHI’m really curious about what will happen. Hopefully people will understand that, for many years, we’ve been overstimulated and traveled too much. Hopefully people will slow down and take the time to reflect upon what actually creates meaning, what the lack of physical cultural spaces actually means to everyday life. Of course, we all can passively watch Netflix by ourselves until we die, but we need other people eventually, no? That’s why I think the idea of the mental fitness center works. If you go to a fitness center, it doesn’t make any sense to try to lift the weights you’re already comfortable with. You have to try things you can’t do. I hope people will understand that the way we have evolved as humanity—for a hundred thousand years—is to try things we don’t know how to do.

A situation like this is quite fascinating, because for the first time in the history of humanity, everybody is scared. I believe a lot of museums will experience a renaissance. I think people will be eager to go back, understand that we have to reconnect, try to normalize. A lot of people will be in search of meaningful experiences, of quality, because they understand that life is fragile. Death and becoming older is the last taboo of modern society, but now we have been talking about that for months. Life is fragile. We will all die, sooner or later. People will say, okay, let’s add some quality to the time I have left.

Museums are a big part of the idea of the Enlightenment, the idea of the nation state, and the story of the welfare state. Institutions will become even more important when it comes to stress-testing the ideas of democracy, the ideas of power structures, of established consensus. If you’re not, then you become complacent and you don’t strive for a better world. Institutions have one role, to question the status quo and strive for a better world. Period.

Mythologies: The Beginning and End of Civilizations, ARoS Aarhus Art Museum, Denmark, April 4–October 18, 2020; photos: courtesy ARoS Aarhus Kunstmuseum