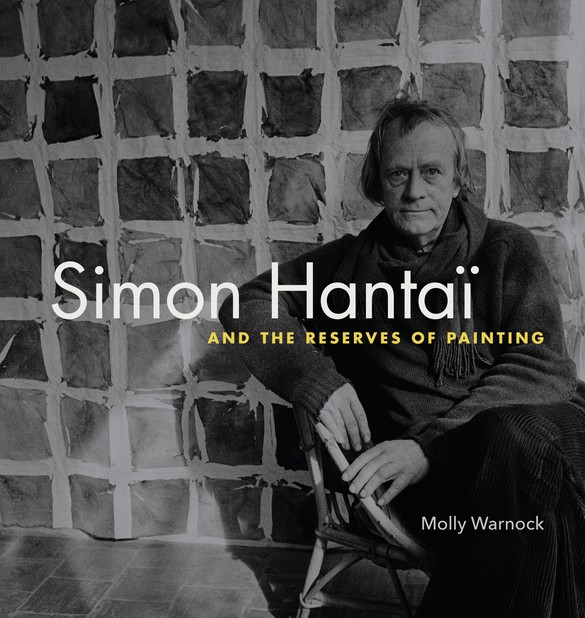

Molly Warnock is the author of Simon Hantaï and the Reserves of Painting (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020) and Penser la Peinture: Simon Hantaï (Gallimard, 2012). She has written widely on modern and contemporary art for, among other journals, Artforum, Art in America, Les Cahiers du Musée National d’Art Moderne, Tate Papers, and Journal of Contemporary Painting, as well as for numerous exhibition catalogues.

This excerpt derives from the fifth chapter of Simon Hantaï and the Reserves of Painting, “The Passage to Pliage.” Where the first four chapters of the book provide sustained readings of Simon Hantaï’s major paintings and writings of the 1950s, the final four deal at length with Hantaï’s major pliage series (works employing a folding technique), along with his post-pliage experiments with digital scanning and printing. Here, I describe the emergence of the artist’s stunning first series of folded and unfolded canvases, the Mariales (1960–62), against the backdrop of his work to date.

—Molly Warnock

Working on the floor of his studio in Paris, the artist crumples an expanse of unstretched canvas. In the majority of cases, that cloth support—usually at least 6′6″ wide in both directions—has been marked in advance with some form of black or dark-brown staining or dripping, much as the canvases in his earlier scraped paintings had tended to be spattered at the outset with high-keyed hues. Hantaï then brushes the visible portions of the partially occluded surface with a coat of primer, followed by one or more layers of industrial oil paint. The whole is left to dry and only later unfolded or, more precisely, pulled from edge to edge to reveal the previously inaccessible zones, thereby shattering the continuity of the painted.

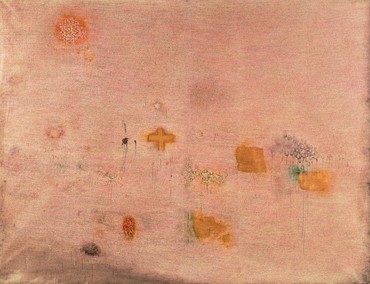

Like the overlapping skeins of language in Écriture rose (1958–59) and related works, the canvas in pliage “cuts into itself,” “invaginates and hides itself.”1 Throughout the earliest Mariales in particular—those of the A and B groups—Hantaï’s tight, edge-to-edge crumpling inherits the allover inclination of the immediately preceding nets of text, even as the thickly applied pigment lends the richly colored crusts newly corporeal heft. Here, the literal relief of the folds—an effect preserved, as the painter noted, by his quick-drying, varnish-heavy medium2 —supersedes the virtual push-pull of the prior scriptural mesh, as do the volumetric effects internal to the colored shards: the crinkling and puckering of the variously pooled paint during the drying process, its spontaneous organization into quasi-graphic configurations. Such works reverse the seeming volatilization of matter enacted by the Souvenir suite and maintained among the shimmering surfaces of 1958–59, converting the mantles of writing in the prior palimpsests into the rough-ridged textures of these newly conceived cloaks.

Elsewhere, as among the works of the C and D groups in particular—and as if to drive home both the adjacency and the difference all the more powerfully—Hantaï’s inaugural suite dramatically confronts a received mode of writing-like marking with the shattered facets produced through folding. Where the underlying, chronologically prior drips and direct staining of the canvas recall the pseudo-Pollockian gestures and spatters of the Sexe-Prime manifesto, an association further encouraged by the return to a more vertical, page-like orientation, the primed and pigmented zones of the superior strata suggest a new kind of “writing,” one in which the obdurate materiality of the support participates fully in a play of spacing. [ . . . ] Like the putative transmissions from obscure regions that Hantaï had been seeking since his Surrealist days, the reserves that appear upon unfolding rearticulate the whole in unpredictable ways. To a far greater extent than with his previous appeals to supraindividuality, however, this surrender is visibly enabled and conditioned by decidedly earthbound materials and operations—such matters, for example, as the heft and resistance of the cloth support; the thickness and opacity of its variously produced folds; and the viscosity and drying time of paint.

Hantaï’s palette participates in this overall displacement of emphasis. A handful of early Mariales, particularly among the near-monochromatic canvases of the A group, extend the sumptuous jewel tones of the previous painting groups: witness the cadmium red M.A.4 (1960) or the rich marigold M.A.2 (1960), to take but two instances employing colors already observable, in far more limited fashion, in Hantaï’s brilliant underpainting throughout the Sexe-Prime suite and beyond. By contrast, later canvases reveal a marked shift toward more naturalizing registers, with various instances conjuring gently troubled water, cracked earth, and leaves, among other associations. Mineral tones prove especially recurrent, as if identifying the artist’s long-standing tendencies toward layering and packing with naturally occurring forms of sedimentary accumulation: consider, for example, M.C.7 (1962), in which a striking azure surface—one of several “Marian” blues that recur throughout the suite—appears shot through with malachite flashes. Here, the canvas “comes down to the ground”—or indeed, “descends to earth”—both figuratively and literally.3

Many of the Catamurons and even the Panses retain these greens, blues, and rusty browns. Yet the two later series also reveal importantly new aspects. The Mariales borrow heavily from Hantaï’s work on already-stretched supports and in carrying forward the immersive, allover effects of the later 1950s paintings—indeed, in liquidating definitively the inherent linearity of writing, a neutralization accentuated by the frequent use of nearly square formats—they are as much the end of something as a new departure. By contrast, the immediately subsequent suites show the painter bringing the edges of the canvas more fully into view, both by shrinking the overall dimensions [ . . . ] and by refocusing his energies on specially emphasized zones. The results inaugurate a new dialectic between a more or less clearly demarcated painted area and unpainted otherness. In retrospect, this is the central event in Hantaï’s post-Mariales practice, the one that drives pliage’s continued becoming as method.

1Simon Hantaï, “Don de tableaux,” in Donation Simon Hantaï, Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris (Paris: Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris, 1998), p. 26.

2Ibid.

3With the move to pliage, Hantaï writes, “La toile descend par terre, devient matériau à interroger” (“Don de tableaux,” p. 26).

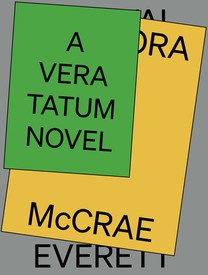

Simon Hantaï and the Reserves of Painting (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2020)

Artwork © Archives Simon Hantaï/ADAGP, Paris