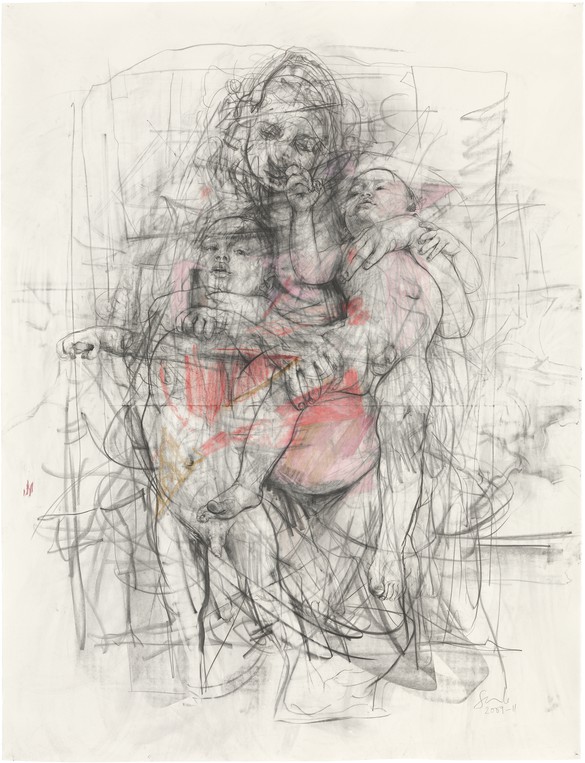

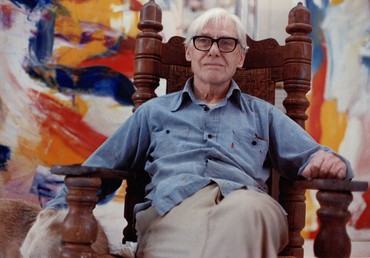

In her depictions of the human form, Jenny Saville transcends the boundaries of both classical figuration and modern abstraction. Oil paint, applied in heavy layers, becomes as visceral as flesh itself, each painted mark maintaining a supple, mobile life of its own. As Saville pushes, smears, and scrapes the pigment over her large-scale canvases, the distinctions between living, breathing bodies and their painted representations begin to collapse. Photo: Paul Hansen/Getty Images

I’ve been working on an exhibition that will take place in Florence next year, that will interact with sculptures and drawings by Michelangelo at venues around the city. One of the exhibition sites is Casa Buonarroti, a museum that houses an astonishing collection of Michelangelo’s drawings and sculptures, as well as archival documents related to his life. When I was last in Florence, Casa Buonarroti had an exhibition of Michelangelo’s correspondence, so when lockdown happened I thought that reading his letters would be a good way to spend the time.

The Life of Michelangelo

By Ascanio Condivi

There are literally thousands of books on Michelangelo, as alongside what he produced, his epic life and struggles make for a good story. I’ve looked at his drawings and sculptures all my life and probably wouldn’t have made paintings like Propped (1992) without seeing the way he made knees push out and twist.

I’ve obsessed about the “non finito” (intentionally unfinished) technique Michelangelo used in his prisoner sculptures such as Atlas Slave (c. 1530). I used the way he constructed a sensual human form from a block of marble as a key to building form out of abstract areas of paint. You can see the transition from nature to culture in a single object. The portrait I painted that is being featured in the Artist Spotlight series was made with these ideas in mind.

The Life of Michelangelo is a famous biography that was written by a former pupil of Michelangelo and published in Rome in 1553, eleven years before the artist died. You can sense Michelangelo’s personal grievances and how he uses Ascanio Condivi to set the record straight and give a factual account of his working life. The book relates details of payments for work, anecdotes from his youth, his fears of assassination and arrest, and his possible plans to live and work in the countryside. When he finished painting the Sistine Chapel, his eyes were so used to looking up that he had to hold letters above his head to read them. You could never describe this book as great literature, but it allows you to get close to the artist and what he wanted to achieve.

The Letters of Michelangelo

Translated and edited by E. H. Ramsden

This edition, published in 1963, is the complete set of the artist’s surviving letters—some 490 in total. A Florentine archivist named Gaetano Milanesi compiled Michelangelo’s letters in 1875, making them generally available. Since then, several books of his selected letters and poems have been published, but I wanted to read the full set of letters and have been working my way through them.

Through these letters, you follow Michelangelo going to Rome at the age of twenty-one and corresponding with his father about sending him his drawings, problems with marble shipments due to bad weather, money troubles, and a nun who claims to be family and wants financial support. The letters cover his movements between Rome and Florence, as well as Bologna and Carrara. There’s a lot of discussion about finances, paying for materials, needing to build roads at quarries, and trying to pin down contracts for commissions. Workers who don’t do what they’re supposed to do are a constant source of frustration, and one letter describes someone moving a block of marble down a mountain and dying from a broken neck.

What the letters reveal to us is that the life force of Michelangelo’s ambition includes the whole process of “taming the mountain” and getting the right marble in the first place—it’s not only sculpting the sculptures and the inner belief that’s involved.

Conversations with Picasso

By Brassaï

This is a great read. In the early 1940s, Brassaï was invited to photograph Picasso’s sculptures, which no one had yet seen. This book of his recollections reveals Picasso’s thinking, his humor and seriousness, and his close attention to the nature of materials, evident in sculptures such as Bull’s Head (1942), constructed from a bicycle seat and handlebars. So many artists try to think like Picasso, but it was the combination of his vivid awareness and his skill level that was where he found all that strength.

Picasso talks about how the Blue and Rose Periods (1901–04 and 1904–06, respectively) protected him and allowed him to be daring without losing his platform of success. When asked where his ideas for drawings come from, Picasso says: “I don’t have a clue. Ideas are simply starting points. . . . As soon as I start to work, others well up in my pen. To know what you’re going to draw, you have to begin drawing.”

Conversations with Picasso also covers the wartime period, during which Picasso worked in unheated studios in Paris and panicked about having enough materials to keep working; his driver became his drawing archivist. As Picasso said, “Read this book if you want to understand me.”

What’s surprising about this book is that it’s difficult to get a copy of it. I ordered a secondhand copy, but you can read it on Scribd with a paid subscription.

Strokes of Genius: Willem de Kooning

Directed by Charlotte Zwerin

If you like painting or want to be a painter, this documentary is inspirational to watch. Made in the early 1980s, it comes from a series called Strokes of Genius, about artists such as Arshile Gorky, Jackson Pollock, and David Smith. This one, on Willem de Kooning, is the one I like the most. It has a lot of footage of his studio in the Hamptons, and of him looking back through his archive and discussing his life and painting. Watching documentaries about artists when I finish work at night has become a habit of mine because it keeps me in the zone but allows me to relax. I wish someone would create a website library of them for artists.

Internet Archive

archive.org

The Internet Archive is an online library of Internet sites and other cultural artifacts in digital form. In addition to digitized books, it contains collections of old newsreels, movie trailers, political campaign archives, websites, and online magazines from around the world. Figuring out how to navigate the interface to find the really interesting content takes a bit of getting used to, but it’s worth persisting, and the content is constantly growing. Its stated mission is to provide universal access to all knowledge, like a contemporary Great Library of Alexandria.